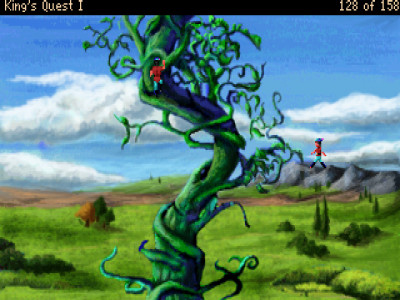

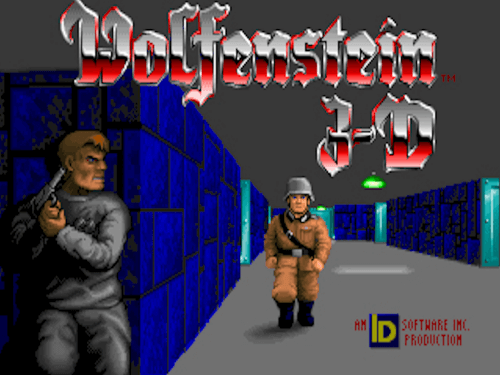

Note: The screenshots posted on this page have been scaled up a little from their tiny native resolutions as well as had their aspect ratios corrected to proper 4:3 dimensions as they should have looked on CRT monitors originally. For posterity’s sake you can also click them to view the “pixel perfect” originals.

Introduction

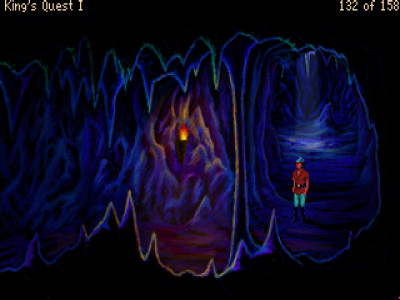

“Wolfenstein 3D”

“…and Spear of Destiny!”

I’d been whining to my poor parents about wanting a new PC for literally years. While it seemed like I might have finally worn them down, I’d do whatever I could to play with any and every kind of computer whenever the opportunity presented itself in the meantime. One of those few opportunities was my 8th grade computer class. The first ever class I had with semi-modern IBM compatible PCs. The class was okay, but the main event was what happened when the last bell of the day rang and our computer teacher’s newly formed ham radio club gathered. For one reason or another, the club almost instantly devolved into most of us just hanging out in the computer lab and screwing around most every afternoon, and we were absolutely fine with that.

Our computer lab was in a pretty sorry state. Other than our teacher’s PCs, which were more or less dedicated to ham and, soon, running our middle school’s official bulletin board system, most of the computers we had were some form of outdated IBM AT clone with zero notable upgrades to speak of. Us nerdy delinquents quickly discovered that one was a cut above the rest, though: a 386 with a VGA adapter and an soundcard. Soon enough, this uber PC got pulled out into the middle of the classroom so we could all gather around it, watching and taking turns playing whatever the latest random game someone smuggled in and managed to get working was.

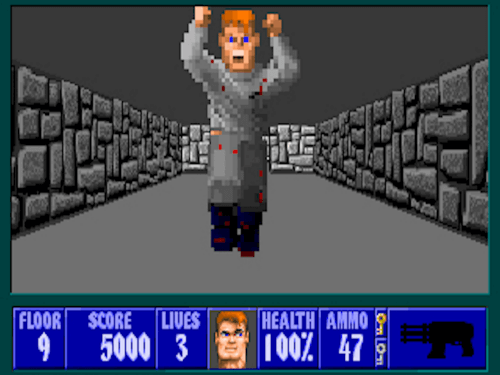

“A showdown with a Nazi guard.”

One fateful day it was the shareware version of Wolfenstein 3D. This machine only had an AdLib in it, so no sound effects, but it didn’t matter. To see Wolfenstein 3D smoothly rendering its glorious violence in full 256 color VGA was utterly amazing. On that day, the obsession I had to acquire a new PC turned into absolute fucking resolve. Wolfenstein 3D was already a year old at that point, and I’d get to see the shareware episode of Doom running (rather poorly) on the same machine before the school year was over, but you can bet when my parents finally caved and spent a ridiculous amount of money on a new 486SX/33 for me that summer, one of the first things I did was drag my mom to Radioshack to buy me a copy of the Wolfenstein 3D shareware disk.

Loading it up for the first time, my AZTECH Sound Blaster clone pumping out that distinctive AdLib soundtrack as my cell door loudly rolled open and I cautiously crept around the corner, pistol in hand, a Nazi guard spotting me and shouting “Achtung!” as he sprang to action, is something I’ll probably always vividly remember, and something that still feels fresh whenever I revisit the game. I loved Wolfenstein 3D! Doom soon utterly overshadowed it, sure, but Wolfenstein 3D will always be the game that introduced me to the now ubiquitous First Person Shooter genre and its masters, Id Software.

“I still have my original shareware version. 3 bucks well spent (even though there’s absolutely no mention on the package that this is only the shareware version… shady!)”

Id Software was formed largely on the back of John Carmack’s technically impressive smooth side-scrolling routines and he soon turned his attention to developing an equally impressive first person ray casting, 2.5D engine which first saw publication in 1991’s Hovertank 3D and a little later, Catacomb 3-D, both released by Softdisk. By the time Wolfenstein 3D was released in 1992, Id had greatly improved the engine, making the controls more accessible, upgrading from EGA to VGA graphics, and adding AdLib music and Soundblaster sound effects. Probably most importantly, they abandoned Softdisk’s subscription publishing model and moved to publishing under Apogee’s shareware model which was already earning them some success with the Commander Keen series. Releasing as shareware meant much, much more exposure, and the game went on to be wildly successful. A commercial only sequel (really, more of a standalone expansion pack) called Spear of Destiny, which I’ll also be covering here, was released by FormGen the following year in 1993, leading to even more exposure. Wolfenstein 3D was a bonafide hit.

Gameplay

Wolfenstein 3D established what quickly became the basic gameplay template for most of the FPS games released in the 1990s. Each level begins in a predetermined location of a self-contained area (usually called a “map” in FPS vernacular) and it’s your job guide your character to the exit. Some parts of the map are behind locked doors which require keys you can pick up along the way, adding a tiny bit of complexity to the exercise. Of course, there are also guards patrolling the map who will shoot you on sight and alert others to your presence if you don’t take them out first. There’s also weapons, ammo, and health scattered around to collect, and unusually for the genre, various treasures that can be gathered to increase your score. It’s a simple formula, and with Wolfenstein 3D’s beautifully performing engine, you can often absolutely blaze through these maps.

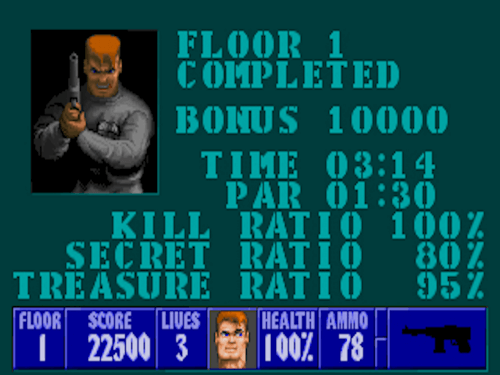

“The end of level score tally.”

At odds with the blazing speed of the gameplay, the score tallied at the end of each mission rewards 100% completion, which includes enemies killed, treasure collected, and “secrets” discovered. These secret hidden areas became a fairly normal part of early FPS design, but Wolfenstein’s are particularly infamous for not being marked or otherwise hinted at in any way. This lead to the stereotype of players running up and down every single wall in every single room and corridor frantically tapping the open key, colloquially known as “wall humping” thanks to how absurd this looks and sounds. That said, without exploring quite a bit, you’re unlikely to get a 100% completion in any of these categories the first time through.

Exploration tends to be unavoidable anyway thanks to Wolfenstein’s labyrinthian maps. While the game starts out with simple designs seemingly based on vaguely realistic floor plans, it quickly goes off the deep end with some gigantic and thoroughly maze-like map designs, and with no auto-map to speak of, getting to the end of these take quite a while and be more than a little frustrating. Navigating the map in the correct order to find the aforementioned keys is the closest Wolfenstein ever comes to throwing puzzles at the player – there are no special trigger areas, switches, elevators, etc. as would soon become staples of the FPS genre. Lack of gameplay variety is not the only problem with Wolfenstein’s maps, as the maps themselves tend to be quite repetitive, with the engine only supporting simple, 90 degree angled walls on a single, level plane.

“Ow. The mutants in episode 2 are fucking obnoxious.”

A bit more challenge comes from the enemies, which are often positioned to strike the second you open a door or go around a corner. While not quite “monster closet” levels of cheesiness, Wolfenstein can occasionally feel a little unfair when it comes to purposely devious placement of enemies, and getting caught by surprise can quickly lead to your death, especially on higher difficulty levels. There’s not too much variety in enemies either, with probably the most crucial variable besides their hit points and rate of fire being how quickly they draw on you in the aforementioned ambush situations.

The variety of your own arsenal is similarly a little slim, with the only thing being anywhere close to exotic being the minigun, which I tend to avoid using during anything but the end of the episode boss fights – the machine gun’s rate of fire is quick enough to effectively stun/stagger enemies but doesn’t chew through the ammo nearly as quickly as the minigun. This is notable, as ammunition can be a little sparse early on which can lend the game a bit of a survival feel, adding some much needed tension to the formula. This mostly falls to the wayside as you progress, assuming you live long enough to hang on to your ammunition supply between maps. These simple, hit scan based weapons do feel pretty satisfying though, which I have to think is a big part of what makes Wolfenstein so damn enjoyable.

As I said in my Duke Nukem 3D review, the old school style of FPS level design ends up feeling quite tedious to me, and in Wolfenstein the simplicity and lack of variety only exacerbates that feeling. As a kid, while playing through the first, shareware episode felt a little bit repetitive, it didn’t really overstay its welcome. By the time you add in the full version’s 5 additional episodes, and if you also play Spear of Destiny, which adds in another 21 levels, that’s a total of 81 levels, never mind the two GenForm bonus mission packs for Spear of Destiny, for another 42 maps, yeah, it’s a bit of a slog.

“Probably the most popular map editor at the time, the aptly named MAPEDIT.”

Surprisingly, a lot of people didn’t seem to think so though, as in addition to Wolfenstein 3D kicking off the FPS genre, it also introduced the world to FPS map making and modding. Wolfenstein’s data structures were quickly reverse engineered and map creation software was released. Given how simple Wolfenstein’s maps are, these editors were simple to use and a lot of people found themselves creating their own maps and campaigns, and a few even dove into editing the sprites and textures, creating some early examples of something close to resembling “total conversion” mods. Personally, I never played around with 3rd party Wolfenstein 3D maps and modifications back in the day, but apparently they were quite popular.

As a quick aside, some of the later console ports of Wolfenstein 3D do make tweaks to the gameplay, from the minor such as differently designed maps, to the more notable ones such as new weapons and even an automap feature. While it’s mostly the DOS version I’m covering here, I still feel this is noteworthy, as some of you might be reading this thinking “What about the flamethrower?” or “What? I used the automap when I played it!”

Story

Wolfenstein 3D doesn’t have much of a story, rather it sets up scenarios and throws you into the action, never really advancing anything resembling a plot. Nevertheless, in presenting you with excuses to be in these mazes, it does at least make an attempt at throwing some fluff in in the form of text introductions and endings to each episode.

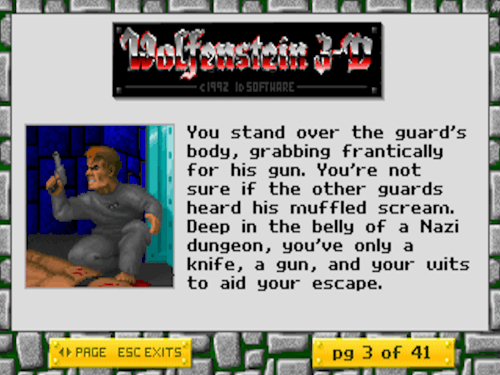

“The introduction to episode 1 (as taken from the in-game readme in the shareware version!)”

“Continued.”

“I’ll definitely tell me grandkids about this.”

Directly inspired by the 1981’s Apple II action stealth game, Castle Wolfenstein, Wolfenstein 3D follows the exploits of allied spy Captain William J. “B.J.” Blazkowicz against Nazi forces in WWII. The most famous of these scenarios, the first episode, has BJ attempting escape from the dungeon fortress Wolfenstein where he was being held prisoner. After that, BJ heads into Castle Hollehammer to stop Operation Eisenfaust – a sinister plot that involves reanimating corpses in an attempt to create the ultimate super soldier. In the third and final episode of the original trilogy, BJ heads to Hitler’s massive bunker complex underneath the Reichstag to put an end to the Third Reich once and for all. This is the definitive set of missions, without a doubt.

The second trio of episodes, snarkily called the “Nocturnal Missions”, are actually prequels, taking place before BJ was captured, in which he attempts to put a stop to a chemical weapons program. These missions aren’t bad, but don’t really add anything essential to the story.

“Spear of Destiny… now with more wall textures!”

Spear of Destiny, on the other hand, is notable because it fully commits to fantasy Nazi tropes, having BJ attempting to stop Hitler from using the occult powers of the legendary holy relic, the Lance of Longinus. He infiltrates Castle Nuremberg and eventually retrieves it, but not before getting transported to hell and having to defeat a demon “Angel of Death” in order to escape. Yes, you go to hell to fight a demon! Wolfenstein REALLY dove into the deep end of the occult stuff here, foreshadowing the full on demonic assault of Doom a year later. Outside of that, again, these missions hardly feel necessary.

Mission specifics aside, the fantasy World War II setting felt fresh to me at the time, especially when combined with Wolfenstein 3D’s immersive first person presentation. Even today, despite how exhaustively the setting and its associated tropes have been mined, the particular combination of pulp comic book action, occultism, zombies, super technology, and real life World War II presented in the original Wolfenstein 3D games feels like a relatively unique blend. I’d guess most people would prefer either semi-realistic World War II settings or even deeper dives into these concepts (as presented in later games in the series) but Wolfenstein 3D’s take certainly was enjoyable.

Oddly, the SNES port of Wolfenstein 3D features a totally reworked plot in an awkward attempt to censor any association with Nazi Germany. All this really accomplishes is turning the antagonists (renamed the “Master State”) into a sloppy and rather obvious analog for Nazi Germany, with Hitler being named Staatmeister and given a shave. Humph!

Controls

Wolfenstein 3D’s controls probably feel totally alien to gamers that grew up after FPS games moved to the WASD + “mouselook” style of control, but what Wolfenstein 3D did at the time set the template for other first person shooters for quite a while: Both hands on the keyboard with your right hand moving you back, forward, left, and right using your arrow keys and your left hand doing everything else with the far left side of the keyboard – Left Ctrl, Left Alt, Space Bar, and Left Shift were typically used to fire, strafe, open doors, and run, respectively. I got used to this control style with Wolfenstein 3D and perfected it with Doom, and had to pretty much force myself into using the newer convention only after it became the norm across the genre.

“Yeah, you shoot dogs in this game. Seriously vicious dogs.”

Granted, part of what makes it work is how simple Wolfenstein 3D is. There’s very little going on outside of moving, firing, and opening doors. You don’t need to (and indeed, can’t) look up and down, nor do you need precision aim since there is a vague aim-assist (or maybe just big hit boxes?) While I’m not sure how it technically works, it’s definitely less pronounced than in latter early FPS games since there is no variation in verticality in Wolfenstein 3D to make it jarringly obvious that your shots are being angled outside of your control.

Still, attempts to get those simple controls mapped to my old Gravis GamePad back in the day never ended very satisfactorily. In the case of the numerous console ports, greater care was put into getting the feel of playing on a gamepad right and thankfully, most of them have various degrees of passable implementations. Again, the simplistic controls make that translation fairly easy. Newer console ports, such as the Xbox Live Arcade version, introduce the modern dual-stick FPS control style to the game, albeit with the right stick only used to look left and right. It sounds weird on paper, but it feels pretty normal and overall I found Wolfenstein 3D to be right at home on an Xbox 360 or Xbox One controller.

“It’s pretty typical to leave a trail of gore in your wake.”

While there is mouse support in the original DOS versions, it’s very rudimentary and won’t satisfy anyone trying to replicate modern control schemes. If you’re looking for that experience, the most popular of the Windows ports of the game, ECWolf, includes support for proper WASD + mouselook, and it works excellently. Like the Xbox 360 port, mouselook is limited to looking left and right, but it still feels fine. In fact, it’s my preferred way to play these days.

Graphics

While Wolfenstein 3D’s graphics aren’t typically the first thing I think about when I look back on the game, I have no doubt that they had quite a lot to do with the game’s success. As mentioned, the Wolf3D engine ran extremely smoothly, even with its VGA textured walls (an upgrade over the original Hovertank 3D) and sometimes large amounts of sprites on screen. Floors and ceilings remained untextured, oddly, but in playing the game this doesn’t really stand out as a deficiency. If anything, it helps the environment feel a little less cluttered than less skilled implementations of fully textured “2.5D” environments in some future games.

“The death animations certainly give a hint of what was to come in Doom.”

The real standout here is the artwork. An obvious precursor to his work in Doom, Adrian Carmack’s colorful, stylized sprite and animation work is a mix between the cartoony and (particularly in the death animations) dark and macabre, and is simply jam-packed full of character. As with in Doom, he really manages to nail the kind of “cool” that appeals greatly to teenage boys, without fully tipping over the edge into being embarrassingly cringy for adults to enjoy. Interestingly, I read somewhere that one of the reasons for Wolfenstein’s distinct, colorful look is that many of the textures and sprites were originally drawn with the limited EGA 16 color palette and then touched up with the engine’s move to VGA, which makes a lot of sense.

I will have to throw in just a little negativity here. While I mentioned the variety in weapons and enemies, as well as the simplicity of the maps already, the lack of variety in wall textures and environmental objects adds to this feeling of repetition to a large degree as well. While there are a fair number of different wall texture sets, it won’t take long until you’ve seen them all. This is huge factor in what makes the maps a little too maze-like, as well – when every room looks the same, exactly how are you supposed to tell them apart? While Spear of Destiny adds a few new textures into the mix, it really feels like a token effort.

“Neat little details abound, like BJ grinning ear to ear when he picks up a minigun.”

Still, altogether, the look of Wolfenstein 3D is quite strong and holds up surprisingly well today, with this lack of environmental variety hurting the gameplay more than the presentation.

Interestingly, the graphics found in the original DOS release were not the only ones around. When the game was ported to the SNES some of the sprites were redesigned, most notably the weapons and your character’s head indicator on the status bar. When ported to the Macintosh, the rest of the graphics were redesigned, redrawn, and/or tweaked, including the enemy sprites and wall textures being drawn at double the resolution for cleaner scaling. The Jaguar and 3DO releases were also based on this version, though again with various tweaks of their own. Opinions on these facelifts vary but it seems like the new graphics in these versions are generally well liked and don’t stray too far from the spirit of the original work.

Sound

From the second the title screen loads and the AdLib rendition of Horst-Wessel-Lied starts blasting, you know you’re in for something different. Like with its graphics, it’s hard to imagine what Wolfenstein 3D would have been without its excellent soundwork.

“Hitler delivering a serious beatdown.”

First, you have Bobby Prince’s soundtrack which is one of my personal favorite examples of classic AdLib music to this day. He manages to combine the sizzling snare rolls of military marches, triumphant anthemic horn blasts, and the intrigue of a good spy thriller into tracks that somehow gel with the feeling of sneaking around these Nazi dungeons almost perfectly. While some of these tunes can get a little repetitive, as an overall package it is very strong.

On top of that you have the Sound Blaster digital sound effects. The first cell door you exit slamming shut behind you, a sound you’ll hear a thousand more times before beating the game, in fact, grabs your attention and puts you at high alert. The gunfire thuds nicely, and the barks of the enemies as they spot you and, with any luck, go down, are awesome regardless of their humorously loose interpretation of German phrases.

“Officers draw on you in and instant, barely giving you time to react to their bark.”

More than just sounding cool, this is one of the first games I recall playing where the sound effects greatly affect gameplay. It’s easy to unwittingly attract enemies to your location while clearing out the map, and sometimes hearing a door open in the distance is your only hint that you’re being hunted. Likewise, almost every enemy “barks” at you the second it sees you, often giving you a few seconds to react before taking fire. Besides helping you avoid getting shot, this can also help identify which type of enemy it is, which can make the difference between life and death. That is, getting caught with your back to a normal guard isn’t nearly as detrimental as letting one of the machine gun wielding SS elite soldiers get a free burst off on you.

Returning to the subject of ports, it won’t surprise you by now to read that the music and sound effects in many of these versions have been touched up or replaced entirely. Most notably, the Mac and 3DO versions have their own, mostly totally distinct, orchestrated soundtracks from Brian Luzietti. While these have an entirely different feel from Bobby Prince’s original soundtrack, it’s hard to deny how great they are too.

Old Age and Alternative Versions

As usual, my primary method of playing through the game for this review was my dedicated 486 gaming PC. I didn’t bother disabling my cache or trying to slow my system down in any other ways, as I recalled it running fine back in the day on a machine only a tiny bit slower than this one. Other than running into some issues with the non-standard way I had my Sound Blaster configured at the time, I had no trouble running it, and it ran just as buttery smooth as expected. There is an issue with secret “pushwalls” sometimes moving further than they should on systems with extremely fast CPUs, but this requires some very specific conditions, thus isn’t a widespread issue.

As for playing it on a modern system, I also played through a significant amount of it in DOSBox. I used the pre-configured version from GOG, although I did have to increase my CPU “cycles” setting to make it run as smoothly as I’m accustomed to. Once I did that, I found that it played quite well. Given that if you acquire Wolfenstein 3D legally from places like Steam or the aforementioned GOG these days, you’re almost certainly going to be getting a copy bundled with DOSBox, don’t forget that you may need to tweak this and maybe a few other things to get the game running optimally.

“ECWolf running smooth as butter in 1080p.”

“ECWolf with the ECMac mod!”

“ECWolf’s automap, as basic as it is, is a godsend.”

That said, I also played through a large amount of the game in the most popular Windows ports of the game, ECWolf. I had only intended on playing through a single episode in ECWolf, but enjoyed the experience so much that I ended up playing through the entirety of Spear of Destiny in it as well. Besides running just as smooth as the original engine, ECWolf natively supports widescreen resolutions, modern WASD + mouselook controls, and includes an automap. It’s hard for me to quantify just how much more enjoyable the game is with an automap at my disposal – it’s a huge quality of life improvement and goes a long way to nullifying my complaints about the the repetitive, maze-life maps. ECWolf also includes some pretty cool drop-in modding capabilities, and I spent some time playing with a mod called “ECMac” which overhauls the original game’s maps with the improved aesthetics of the Macintosh version. Extremely cool.

Finally, I also played through an entire episode in the Xbox 360 / Xbox Live Arcade port of the game (on my Xbox One.) Despite some well-known issues with the music and some very minor texture changes, I found this version to be faithful to the DOS original and a fair representation for new players wanting to check out the game without dealing with getting it to work on a PC. As noted above, playing it with dual sticks on a modern joypad is a little odd at first, but I got used to it extremely quickly.

“The SNES version looks passable up close.”

“But the scaling is extremely harsh. You can barely make out the guard here!”

“The 3DO version, on the other hand, is mostly excellent.”

There are, of course, other ports. I mentioned some of the original console and PC ports: SNES, Macintosh, Jaguar, 3DO, and oddly, the Apple IIGS. There were also later ports to GBA and IOS, and unofficial ports for a number of systems, almost reaching Doom’s ridiculous levels of ubiquity. Some of these ports include their own maps and other odd changes that could be worth looking into for the truly dedicated. There are also some hidden versions and throwbacks in newer games, such as the original Xbox port included with Return to Castle Wolfenstein: Tides of War, and the cool little appearances in Doom II, Wolfenstein: The New Order and Wolfenstein: The Old Blood, and Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus… too cool!

The original game manuals are available when purchasing the game and various other sources, though besides being a straightforward introduction to the game, they’re not really required. You can also find the official hint books that came with boxed copies of the games around too. These hint books aren’t too useful outside of having detailed diagrams of every map in the original game, but they’re fun to flick through and even include some bonus vintage pictures of the Id Software guys.

Sequels and Related Games

Id Software moved on to Doom almost as soon as Wolfenstein 3D was out the door, and most wouldn’t consider Spear of Destiny a proper follow-up. It wasn’t until almost 10 years later that Gray Matter Interactive put out Return to Castle Wolfenstein, rebooting the series with some success. It was almost as long for it to get a sequel, the Raven Software developed Wolfenstein in 2009. In 2014, we finally got the acclaimed Wolfenstein: The New Order which continues the series, and it’s prequel, Wolfenstein: The Old Blood, which is somewhat of a re-imaging of the events of the earlier titles. The New Order got a proper sequel in 2017 with Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus. Along the way there was also Wolfenstein RPG for mobile devices, though I never got to play that one before it dropped off the face of the earth.

“While the guard is slow to react, the SS soldier is about to drill me.”

There were also plenty of other games that used the Wolf3D engine and its derivatives. Besides its predecessors, Hovertank 3D and Catacomb 3-D, the sci-fi Blake Stone: Aliens of Gold and its sequel Blake Stone: Planet Strike are favorites of mine and I’ll likely cover them here some day. There’s also the much less enjoyable Operation Body Count and Corridor 7: Alien Invasion, and the infamously bizarre Super 3D Noah’s Ark for SNES. Using a heavily modified version of the engine, Apogee’s Rise of the Triad: Dark War actually started life as a sequel to Wolfenstein 3D, and some hints of that exist in the game as-released. Finally, straying off a little more, technically, the Raven Software developed Shadowcaster used what was a bit of a stepping stone between Wolf3D and the Doom engine, AKA Id Tech 1, kicking off a long history of association between the two companies.

Closing

“The camera zooms out to show you in 3rd person as you exit an epsiode. Awesome touch!”

It’s honestly been a treat for me to head back into the corridors of Castle Wolfenstein and to see just how closely my memories of blasting Nazis and hording treasure hold up. I think others who remember Wolfenstein 3D and other, similar early FPS games fondly will potentially enjoy playing the game too, at least until its repetitiveness wears out its welcome. That said, if you were brought up on newer FPS games with frilly extras like “stories” and “mechanics” its hard to imagine Wolfenstein 3D keeping your interest even that long. It’s a highly influential, well polished, fun, but at the end of the day, very limited game, and it was improved on in just about every conceivable way by Id Software’s follow-up, Doom, and the long line of first person shooters that followed it. Outside of the nostalgic and those interested in FPS history, it’s unlikely to entertain all that much, sadly.

Bummer of an aside: While writing this and reminiscing about my old middle school computer science class, I thought it might be fun to track down my teacher and thank him for being an influence in my own successful career in information technology, only to discover that he passed away in 2012. Pouring one out for you, Mr. Miller!