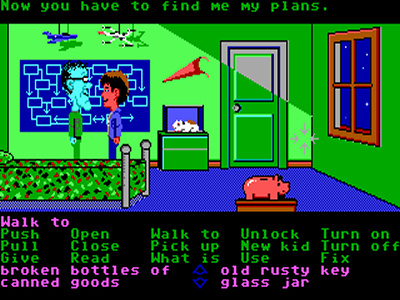

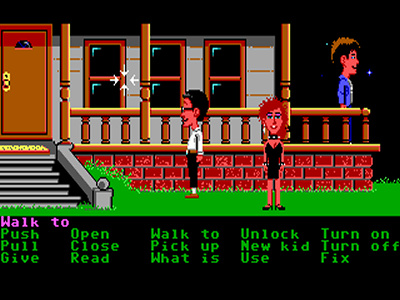

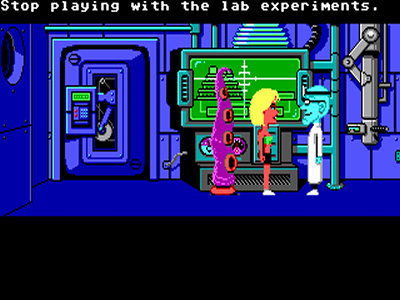

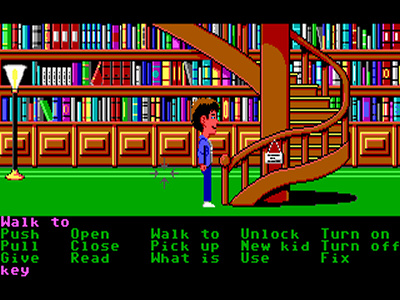

Note: The screenshots posted on this page have been scaled up a little from their tiny native resolutions as well as had their aspect ratios corrected to proper 4:3 dimensions as they should have looked on CRT monitors originally. For posterity’s sake you can also click them to view the “pixel perfect” originals.

“Maniac Mansion!”

Introduction

In my last review (The Hugo Trilogy) I mentioned my fondness of old adventure games and Maniac Mansion is perhaps one of the most important adventure games of all time. Maniac Mansion was first developed by LucasArts (then LucasFilm Games) all the way back in 1987 and was one of the company’s very first adventure games. It was also the first game to use the much loved SCUMM engine which would go on to power just about all of future LucasArts adventure games – SCUMM, in fact, is an acronym for Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion. Being the first SCUMM game also makes it one of the first “point and click” adventure games. It’s also notable for being widely spread across different platforms, even showing up on the Nintendo NES of all things, albeit censored. As an NES game it’s gameplay and themes were fairly unique and undeniably influential.

“Man, Weird Ed is one dedicated peeping tom.”

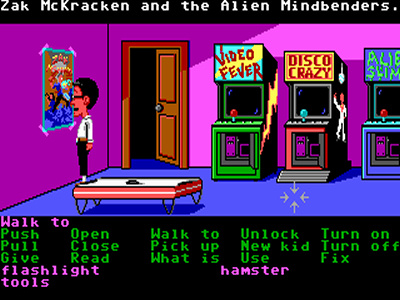

As for my part I never actually played the game when I was a youngster which may help explain why this review is much more analytical in tone than most of the other Maniac Mansion reviews floating around the ‘net. My first exposure to it was probably seeing an advertisement for it in an old gaming magazine. The ad was primarily just the box art, but it was intriguing nonetheless. I also distinctly remember reading about the ability to microwave a hamster in a walkthrough published in an old Gamepro or maybe even Nintendo Power. I was in awe of how many different, seemingly complicated actions the character could make… and a game where you could microwave a hamster? Come on, this stuff was a young boy’s dream! I even recall talking about this amazing hamster scene with another kid at school, who claimed to have owned the game and zapped that poor little guy a time or two himself.

The next time wasn’t until Maniac Mansion’s sequel Day of the Tentacle was released in 1993 which was right around the time I first got hardcore into PCs. It seemed like everyone had Maniac Mansion fever and there were a million magazine articles, BBS posts, etc. about both the new game and the original. This great wave of hype is what reminded me about the game and eventually inspired me to finally play it.

Gameplay

Beyond the innovative SCUMM engine, which I’ll talk more about under the Controls section, I actually feel like Maniac Mansion deserves quite a lot of credit in the gameplay area. Most 2D adventure games feature a linear progression of screens via puzzles with only one solution, finally culminating in a single ending. Not only does Maniac Mansion feature multiple endings but there are multiple paths to take throughout the game, and even multiple ways to solve the individual puzzles. For a game that is so often considered a prototype for point and click adventure games very few have followed suit in this respect, sadly.

Unlike most adventure games in which the player guides the protagonist through screens solving puzzles to unlock the next series of screens and puzzles, Maniac Mansion immediately plops the player down into a large, open area which they can explore more or less freely. Sure, there are still items to collect and puzzles to solve, and you bet some of these puzzles allow the character to advance to new screens, but the entire setup feels very freeform in comparison.

“Foreshadowing a future review? I think so.”

Beyond the obvious positives to this such as the sensations of freedom and choice, unique player experiences, and a high level of replayability there are also some negatives.

First time players won’t have much of an idea of what to do next or even what their goals are beyond rescuing the main character’s girlfriend. Like I said, you’re simply dropped in front of the mansion and told to have at it. While a lot of the puzzles reveal themselves in time others are much more obscure thanks in part to how widely dispersed items and clues often are. Almost every puzzle has at least some kind of clue suggesting its solution but most, though logical, are incredibly vague. Of the items the fact that many are red herrings doesn’t make the whole process of discovering and solving puzzles any easier either. Let’s also not forget that many of these individual puzzles can be solved in almost any order, further muddying the water.

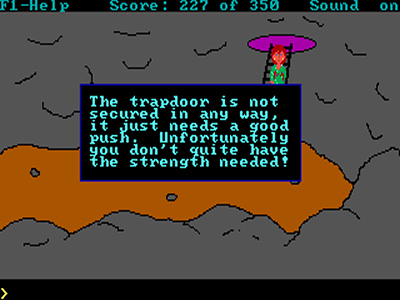

Here’s an example of annoying red herrings and vague solutions. There’s a drawn out chain of puzzles towards the end of the game in which one of the steps is to feed a Venus Flytrap radioactive water in order to get it to grow up to the ceiling so that you can reach an otherwise inaccessible trap door there. Logical, eh? Still the Venus Flytrap becomes a deadly man eating plant after it’s growth spurt and climbing it ceases to remain such a novel idea. The solution to this puzzle is to pacify it by giving it a can of Pepsi. Why a Pepsi? Who knows! There’s a variety of other food and drink in the house, much of which are of the worthless red herring variety, yet it’s only Pepsi that satisfies it enough to keep the giant man eating plant from devouring our character? Alrighty then.

“Speed limits in space? The future is depressing.”

Indeed, I would imagine that most people that played Maniac Mansion without the aid of a hint book or some other walkthrough either didn’t beat it or spent hours upon hours experimenting through dozens and dozens of playthroughs. Restarting is definitely something you might find yourself doing in Maniac Mansion – unlike most future LucasArts adventures you can suffer from instant, trial and error deaths, getting tossed into the dungeon, and other setbacks such as missed, one time opportunities to acquire certain items or using them the wrong way and wasting them. You can even become stuck unknowingly unable to complete the game due to losing an item. The game is challenging – even an adventure veteran like yours truly felt lost time and time again the first time I ever played it.

Eventually the player will probably reach a point in which they’ve gone through a lot of work acquiring all kind of items but aren’t much closer to rescuing their character’s girlfriend. By then, however, they’ve hopefully noted several clues from all kinds of sources pointing in several seemingly unconnected directions about how to put the pieces together and how to proceed. Once you solve the last few puzzles, or at least know what they are so that you can restart and focus better on how to solve them, the game seems much, much simpler.

There’s another interesting layer that I’ve yet to mention. The player controls not one character but three. You only control one at a time but can switch between them at will. This leads to some puzzles that require more than one character and, perhaps more importantly, some opportunities to do some multitasking by having one of your characters, say, distract an NPC while another raids the room the NPC was in, all while a third waits somewhere strategic for some other event to go down.

“I hope his plans involve a face lift, a makeover, or something. Yuck.”

The twist is that while the majority of the puzzles in the game involve collecting items from the game world and using them in conjunction with the environment or each other in typical adventure game style, only certain characters have the ability to use certain items in certain ways. Of course, keeping with the precedence for being vague the game never makes this exceedingly clear. You can pick 2 out of 6 characters at the start of the game. While this means some characters are the only ones who can complete some puzzles, puzzle chains, or even entire paths no single character is ever required to beat the game. Again, there are multiple ways to reach the end and often enough multiple ways to solve individual puzzles.

Still, a little challenge isn’t always bad, right? Ultimately I think Maniac Mansion works best as a game you sink a huge, huge amount of time into experimenting with. A lot of people probably had a ball with this game when they were kids with tons of free time but it’s hard to imagine myself playing it that way these days. If you decide to take the easy way out I’d highly recommend you shy away from detailed walkthroughs and instead look into more obscure hint guides such as the UHS program with it’s multiple levels of hints to point you in the right direction rather than just bluntly telling you what to do. This way the exploration and experimentation facets of the game will stay intact without you having to spend your whole childhood figuring out how to get into the Dr. Edison’s laboratory.

Story

A meteor crashes down near the mansion of Dr. Edison. Dave leads a search party consisting of his teenage friends into the mansion in search of his kidnapped girlfriend Sandy. Meanwhile Dr. Edison appears to be holding Sandy in captivity in order to hook her into an insane looking machine to do something with her brain. This is B movie comedy sci-fi/horror type stuff. Boxed copies of the game come with a poster that has some more interesting tidbits on it, mostly serving as vague hints, that add slightly to the background. That’s about all we know as the game starts and little else is learned throughout the course of the game. Not unlike the last batch of adventure games I reviewed (The Hugo Trilogy) Maniac Mansion doesn’t have much of a plot to speak of, rather it relies on setting up a scenario and a setting in which it takes place and we’re left to explore this environment on our own.

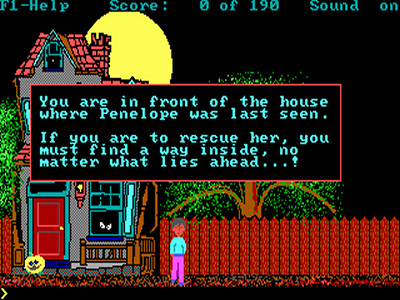

“Breaking and entering…”

That being said Maniac Mansion does do quite a bit better when it comes to presenting an interesting setting than the aforementioned games. The Edison mansion is filled with odd characters such as Dr. Edison’s sex starved wife and the infamous sentient tentacles and other strange attractions like the nuclear reactor in the basement. Maniac Mansion also occasionally uses cutscenes to advance development a bit letting you learn more about the inhabitants and their situations. You’ll also learn more about them through the puzzles themselves as several of them involve having to work with these characters in order to progress – by the time the game ends you’ll definitely have learned (a little) more about what Dr. Edison is up to. Unfortunately player characters themselves are barely fleshed out at all beyond what you’re told about them on the character select screen.

There is little conversation outside of this cutscenes since the game doesn’t feature an option to talk to other characters. The game is also sorely missing a “look at” type command which would have offered many, many more opportunities for witty dialog. Despite this the game still manages to be quite funny with its dark yet quirky characters and numerous little humorous touches. Still, I can’t help but concluding that in the area of story it falls quite short in comparison to later LucasArts adventures.

Controls

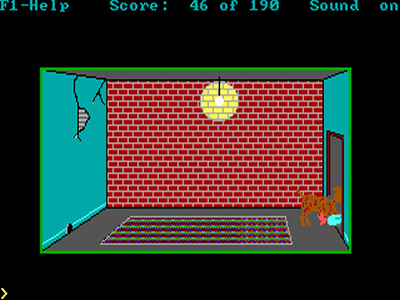

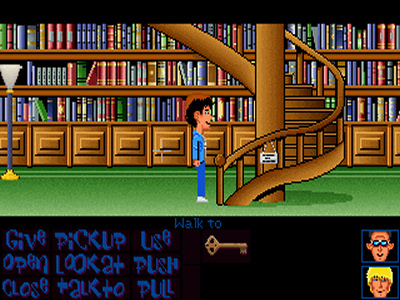

The SCUMM engine chops the screen up into several parts. On the top we have various messages, more often than not descriptions of events taking place. In the middle, occupying most of the screen, we have the animation window that shows us our pretty graphics. Just below that we have our command sentence text, below that our list of commands, and finally our list of items.

The characters are moved around the screen by clicking where you want them go. It works well enough most times though thankfully there aren’t any crazy movement puzzles to put the movement controls to the test in Maniac Mansion unless you count some of the occasions in which you might be trying to frantically run from NPCs.

The rest of SCUMM works by attempting to emulate old text parser games by letting the player “build” their text commands with their mouse, more or less. For instance, instead of typing “use key in door” you might pick the “use” option from the command, or, more accurately verb list, then pick the key from our item list, inventory, or, again to use SCUMM terminology, noun list. This will write “use key with door” in our command area, the command executing.

“Two tentacles square off. Man, that was weird to type.”

This might lose me a few readers but I’ve never claimed to be a big fan of the SCUMM interface in general, despite the many amazing games that use it, and I actually prefer Sierra’s SCI engine which takes us even further away from the old text parser days. SCUMM did improve, no doubt, but this is its first implementation and it has several issues.

First of all, as mentioned above there is no “look” verb. Virtually every adventure game, text and point and click, spews a huge amount of dialog out about items, environments, and characters. Not in Maniac Mansion! This is a real disappointment as I can only imagine how hilarious some of these descriptions might have been. Similarly, and again already noted, Maniac Mansion is also lacking any kind of “talk to” verb so no conversation trees in this game!

Pixel hunting for items that can be picked up or otherwise interacted with is also much more difficult in this version of SCUMM. Instead of just being able to roll your mouse over anything you have to choose the “what is” verb to identify them. This can be especially tedious in the game’s many darkened rooms.

There’s also the fact that there seem to be way more verbs than needed. Do we really need to differentiate between “open” and “unlock”? If you’re going to open something that’s locked you’re going to unlock it in the process, right? “Turn off” and “turn on”? Why not just have a single “Turn on/off” command? Really, almost all of these commands could be whittled down into a single “use” verb in my opinion.

Later SCUMM games address all of these complaints and even go on to make other changes, such as making the inventory graphical, but this is the first one and it sure beat typing.

Although I’m not reviewing the NES version here it is worth mentioning that the controls of the NES version are the same save for the fact that the digital pad is used to control the mouse pointer. While not quite as quick or as accurate as an actual mouse this usually works well enough.

Graphics

This game has been ported all over the place (notably the other big players at the time, Amiga and Atari ST) but since I’m concentrating on the PC version those are the graphics I’m going to talk about. The PC version actually came in two distinct varieties.

The first, EGA version which was released in 1988 came more or less directly from the original Commodore 64 version. The graphics are simple and blocky with strong colors thanks to the limited 16 color palette. The character sprites are actually fairly large even if they are simple looking. Personally they kind of remind me of the way Terrance and Philip and other Canadians from South Park look. 😉 Animations are extremely simple featuring only a couple of frames for walking, for example.

“The original version.”

“The enhanced version.”

“Maniac Mansion Deluxe.”

“The NES version.”

The later “enhanced” EGA version released in 1989 features very similar artwork with much more detailed sprites and a better use of the color limit. This version is a definite improvement over the original one though it isn’t a dramatic departure. Probably the most remarkable thing about the upgrade is that the characters sprites have much more personality thanks to them remaining relatively large, allowing for more detail. While the enhanced version definitely isn’t as pretty as later VGA adventure games with their hand painted backgrounds and colorful sprites it does seem to possess a charm of its own.

While I’m at it I’ll also mention the NES version yet again. The NES version of Maniac Mansion’s graphics are entirely distinct from any other version of the game that I know of. Literally every sprite is different and the screen backgrounds are completely redrawn as well, sometimes radically. Putting them side by side, other than the art style changing the sprite and backgrounds are all scaled down and condensed as well. While some people might actually prefer this version it probably falls somewhere squarely in between the original and enhanced EGA PC versions in my opinion. As an aside there’s also a version with more manga inspired character sprites for Japanese audiences… bizarre!

Sound

Both PC versions of Maniac Mansion make similar limited but careful use of the PC speaker for sound. Quieter and less harsh than a lot of PC speaker sounds the effects are used sparingly but fairly effectively – we’re talking little things, such as the ticking of a clock, the clicking of a button being pressed, doors opening and closing – you get the picture. These stand out, when present, thanks to the lack of any ambient background sounds or any sort of soundtrack. There is a short intro song and some other, more interesting sound effects such as when the piano is played, but for the most part PC speaker use is tastefully conservative.

“Indeed, Dr. Fred.”

The NES version, as you might imagine, has radically different sounds. In addition to sounding different effects are used a little more frequently and with more variety. The biggest difference about the NES version, however, is that it actually does feature a background soundtrack. Each player character has its own theme song that loops while you’re controlling that character. It’s a pretty neat feature and the tunes are varied and decent though they’re all a bit too short, looping too frequently for my tastes.

Old Age

As usual I played both versions of the game on my dedicated gaming 486, much of the time without worrying about disabling my internal cache or artificially slowing down my machine further via any other method – as far as I can tell Maniac Mansion is free of CPU speed timing related bugs. Maniac Mansion won’t play nicely with any modern OS however so DOSBox, which it is apparently 100% compatible with, is needed.

Alternatively, SCUMMVM is a similar program that can be used to run all of LucasArt’s SCUMM games (and some others) and has been ported to just about every platform out there. If you’ve ever heard whispers of people playing adventure games on their Sony PSPs or Nintendo DSes this is what they were using to do so. I’ve personally yet to try SCUMMVM but I’ve heard great things about it. Apparently you can just drop the SCUMMVM executable in your game’s program directory and run it instead of the original executable file – much easier than tinkering with DOSBox for most people, I’d think.

Legally acquiring Maniac Mansion can be difficult as LucasArts hasn’t made any of its back catalog available for quite a few years now for some mysterious reason. The easiest way to get your hands on it would probably be to track down a copy of the NES version, which isn’t too rare – eBay has a dozen or so at the time of this writing for between ~5 and 15 dollars, many of which include the manual and packaging. Another option is to acquire Maniac Mansion’s sequel Day of the Tentacle – As a very generous easter egg the entire Maniac Mansion is playable from within the game on Ed’s computer. Day of the Tentacle is a little more rare but can be found on eBay for only around 20 dollars when it shows up and is an amazing game in it’s own right.

Update 3/2016: Day of the Tentacle Remastered is now a thing and available legally on various platforms. Like the original version it includes the original Maniac Mansion as an easter egg.

Finally, the easiest way to acquire Maniac Mansion is to not worry about acquiring Maniac Mansion at all. Instead, seek out Maniac Mansion Deluxe. Maniac Mansion Deluxe is a freeware fan remake of Maniac Mansion in which the entire game was painstakingly recreated using the excellent and widely used Adventure Game Studio. All of the graphics from the enhanced version have been touched up, recolored using a 256 color palette and an infatuation with gradient shading, and reanimated. Maniac Mansion Deluxe also barrows the updated SCUMM interface from Day of the Tentacle meaning less/different verbs, a graphical inventory, and a graphical character swapper. It also adds background music and new, improved sound effects amongst many other features.

“Maniac Mansion Enhanced.”

“Maniac Mansion Deluxe.”

Perhaps the best thing about Maniac Mansion Deluxe is the simple fact that it is actually a modern Windows program meaning it should run on newer PCs running newer operating systems without the need to toy with extra programs or settings. The AGS engine itself offers some other added modern conveniences. For instance, my LCD monitor doesn’t support scaling up a tiny 320×200 VGA resolution screen however with Maniac Mansion Deluxe I can choose to scale it up to 640×400 (or 640×480) which my monitor will gladly run in full screen. You can, of course, also use this feature to run the game windowed without the window being amazingly tiny. Newer AGS games offer a broader range of configuration options, such as more scaling choices, but what Maniac Mansion Deluxe provides should be sufficient.

I can’t speak for how accurate of a recreation Maniac Mansion Deluxe is exactly as one would need to play through it exhaustively to know if every screen and puzzle was correct but from what I have seen it appears to be a faithful remake with just a few minor additions and changes.

The manual and other documentation is only needed for getting around the copy protection in the enhanced PC version of the game, otherwise it is fairly useless. I’m sure this can be cracked out once the game is installed however. The included poster does have some interesting background information and subtle clues, as I mentioned earlier, but nothing you need. Still, you can find it and a million walkthroughs all around the ‘net thanks to this game’s hardcore cult following.

Sequels and Related Games

I suppose you could say that most of the SCUMM games are at least somewhat related to Maniac Mansion. Still, as mentioned various times before now, LucasArts followed up Maniac Mansion with an actual sequel, the excellent “Day of the Tentacle”, in 1993. I’ll save the details on that for a later review!

Closing

Maniac Mansion certainly isn’t a perfect game but what it does differently, and indeed what it did first, earns it the great reputation it has in the realm of classic games. As the introduction game to the SCUMM engine just about everything innovative it does in that respect has since been improved upon – there are other games I’d recommend over Maniac Mansion as a demonstration of SCUMM. As an adventure game, however, it is fairly unique in it’s non linear, open design. True, I’d probably recommended a more linear, story driven game to an adventure game neophyte but if you’re already a big fan of old school point and click adventure games and somehow have yet to play Maniac Mansion than you should definitely check it out if not for its historical relevance alone. The impact this game made, both on its fans and the evolution of PC gaming, cannot be denied.