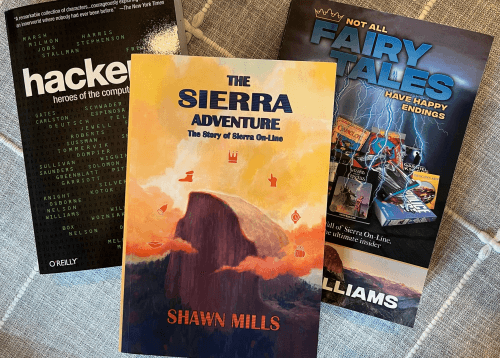

Returning to something more traditional for my partner and I, the good old narrative heavy modern take on the adventure game, which we’d played so many of together over the years, we played our very first ever Supermassive Games title, The Quarry. Supermassive is probably best known for its PlayStation exclusive Until Dawn, and from what I gather, there are quite a lot of similarities between the two games – I’d even read that The Quarry was the product of an aborted attempt to make an Until Dawn 2. For better or for worse, since I’ve yet to play Until Dawn, I won’t be tempted to fill this entire review with those kinds of fun comparisons. They’ve also got the Dark Pictures Anthology series, which I gather consists of similar, though smaller and generally less ambitious games that each tackle different horror subgenres.

“In true horror movie style, it doesn’t take long for shit to get real.”

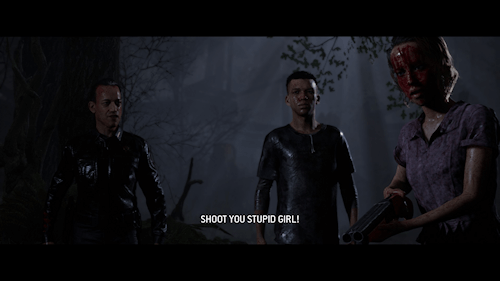

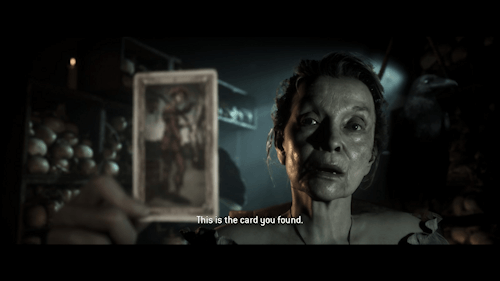

Like those titles, The Quarry is also a horror game. I went into it somewhat blind, and was pleasantly surprised by having my assumptions about what the game was about quickly challenged – judging it by descriptions I’d read and trailers I’d seen, it looked like your stereotypical Friday the 13th style slasher affair. You know, a bunch of teens at a summer camp in the woods getting picked off one by one by a deranged psychopath, that sort of thing. It is that, but, being vague so that others might have the same experience as I did, it also, almost immediately, introduces monsters, witches, and weird Southern family tropes, which kept me guessing about where the story was actually going (at least for a little while) while being appropriately creepy throughout.

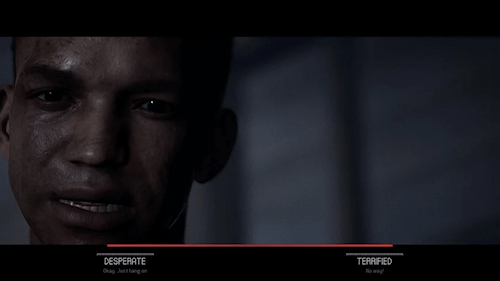

I have to say that The Quarry, overall, looks fantastic. The graphics are fairly realistic to the point of occasional moments of “uncanny valley” when it comes to those trickier to nail things like facial animations. Even more so because of their preference to base character faces on their actual voice actors, including some you’ll likely recognize – David Arquette’s character was featured heavily in promotional material, for instance. Overall though, the game looks really, really good. For the most part, the UI, hell, the entire presentation of the game, is also really nice and quite polished. Being that this was my first Supermassive game, I didn’t quite know what to expect in terms of quality, but this definitely feels a million miles away from your stereotypical low budget PC-only modern adventure game. Oh, and the audio here is all great too – the effects, music, and voice acting are very good, and more importantly, they’re all used really effectively too. On a technical level alone, most of my hesitation about jumping onto the Supermassive bandwagon quickly disappeared.

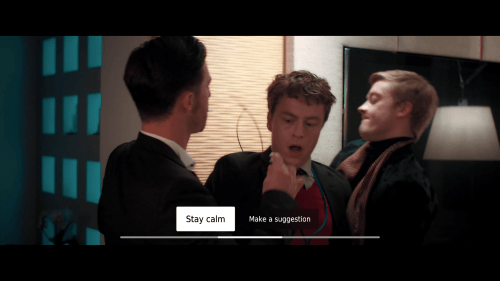

“Choices are usually binary and often timed.”

Gameplay-wise, The Quarry feels like a weird melding of your minimally interactive modern FMV or “interactive movie” games, like Late Shift, your old school, very interactive point and click adventure games, and the middle ground, something like Telltale’s Walking Dead series, for example. I think it works quite well, providing opportunities for puzzle solving and even action sequences as well as dialog choices and other decision making, while leaving a ton of room for setting the scene or advancing the narrative via long cutscenes. Interestingly, you’ll be jumping between playing each of a group of camp counselors, and the co-op mode lets you assign who plays which specific characters, and even lets you divide up the entire cast to different players via the online “Wolf Pack” mode. My partner and I divvied up the characters based on their profiles and swapped the controller as needed, which, in terms of who gets to play for how long, was more than a little random at times, but was fun and more tonally consistent than having to take turns making sometimes contradictory decisions as the same character.

“YESSS! A game the ridicules me for missing useless collectibles!”

I’m still of two minds over whether this is a actually bad thing, but sometimes these major branching moments didn’t come about by an obvious decision. For example, early in the game there was an action scene where, if we had reacted quickly enough, we could have killed a character which would have had a huge effect on the rest of the story, and the fact that this was based on a semi-twitchy, high pressure scene definitely caught us by surprise. Oh, and speaking of which, yes, major characters can die or be affected in very big ways that have ramifications throughout the rest of your playthrough, which was one of the charms of Telltale’s adventure games as well, and feels cranked up to 11 here. I understand this was also the case with Until Dawn and most of Supermassive’s other adventure games, and while this could be criticized as being gimmicky, personally, I’m a fan.

I can’t say I absolutely loved every character or every story beat, plus the ending felt a little sudden, which sadly isn’t an uncommon issue in these types of games. In this case though, I could definitely see myself playing through it again one of these days, especially given all of the fun extras and collectibles and the insane amount of deviation and branching your choices and actions can bring about – apparently there are 186 variations of the ending available. As I said, insane. In the end, we enjoyed it enough to buy the entire first season of the Dark Pictures Anthology the next time it was on sale. ‘Nuff said!

Next up, wanting to play an actual cooperative game on PC that wasn’t yet another tree punching survival game, I came across the We Were Here series of asymmetrical co-op games. Now, we’ve played a few co-op focused games, most notably the Hazelight ones, but reviews made We Were Here sound like it was much more likely to test the strength of our relationship. Now that’s true horror! 😅

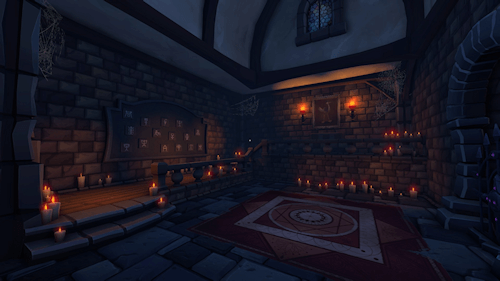

“A creepy castle filled with creepy puzzles.”

The setup is simple: Without much further explanation, you and your partner are walking with a larger group through a frozen wasteland and split off to check out and then take refuge in a mysterious castle. The next thing you know, you’re both waking up to discover that you’ve been split up. One player takes the role of the “librarian” whose primary job is to, confined to a small area, reference books and other useful objects spread throughout. The other player is the “explorer” whose job it is to, well, explore. That mostly involves navigating from room to room and investigating the mysteries therein, which ultimately lead to the way to the next area, like multiple relatively simple escape rooms chained together. Each player is given a walkie-talkie near the beginning to communicate with one another (using in-game VOIP, a feature I always really like even though I usually eventually end up abandoning for out-of-game voice chat) and from then on, the game is on.

Naturally, communication is key to solving these puzzles – the explorer might need to describe symbols or pictures to the librarian, or vice versa. That communication needs to actually be good too, as a lot of the things you’re asked to describe are intentionally extremely similar, so the players need to be detailed to avoid mistakes. There are also puzzles that involve one person helping the other person navigate through mazes, and as typical as that sounds, a lot of these scenarios have some pretty clever twists. Look, I grew up in the UK in the 80s and 90s and watched a ton of Knightmare, so I was more than up for the challenge. (If you know, you know!)

“Guiding the Explorer around a maze as the Librarian.”

While obviously done on a budget, the presentation is pretty good, featuring the same kind of low polygon, colorful, stylized graphics I mentioned learning to love with Firewatch when describing a lot of other games recently (I really need to find a term for this style…) and yet it manages to be quite creepy a lot of the time too. It’s definitely a vibe, and your mileage may vary, but it works for me.

Interestingly, the whole thing only lasts a couple of hours, though you’ll likely want to switch roles and play it a second time, especially if you’re into achievement hunting. Still, the game is often free, and as such, makes a perfect demo for the rest of the series. That strategy certainly worked on us – we were impressed with it enough to immediately turn around and purchase the sequel, We Were Here Too, which I’m sure I’ll talk about here eventually.

Finally, we’ve just completed our playthrough of The Council. The Council is an episodic narrative heavy adventure game developed by Big Bad Wolf, who are probably best known for their later take on the Vampire: The Masquerade universe with Swansong in 2023. I don’t know too much about Swansong, but it appears to use a lot of the same gameplay mechanics as The Council, though it has significantly worse reviews. Hmm. 🤔 This might just be a result of The Council attracting more of a niche, adventure game loving audience than Swansong, which probably attracted a lot of players hoping for a sequel to the cult classic Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines, which it clearly is not.

“If you think these guys are ugly, you should see Sir Gregory Holm!”

I distinctly recall having some hesitations about this game when first coming across it on the Microsoft Store, but my partner was very intrigued and its reviews were surprisingly positive, so we eventually purchased it. It’s funny, we played them far enough apart that I didn’t really compare it to The Quarry while playing it, but now writing this compiled review, I can’t help but to weigh them against each other, at least a little, given that they’re in the same genre of gameplay. On the surface, this does not bode well at all for The Council, but in some ways, The Council is actually much more interesting.

The main reason for my hesitation was the visual presentation. Screenshots and trailers made this game look almost comically bad looking. You have a variety of historical figures, like Napoleon Bonaparte and George Washington, with ugly, stylized character models, and hey, there’s some kind of a murder mystery or something afoot too? Seriously, what the fuck is this game?! While I have to stand by that initial impression of the graphics, particularly the character faces, as being bizarre, sometimes exaggerated to the extent of being grotesque, overall, I actually came to enjoy the style once I got used to it. This will no doubt be a divisive point though – I’d expect a lot of people will absolutely loath them. That said, the scenery, particularly inside of Lord Mortimer’s mansion, where you’ll be spending the majority of the game, was well executed. Really, the only technical issues with the visuals are around the character animations, which range from “eh, decent I guess” to utterly abysmal. Well, actually, the bottom of that range would be “not there at all” as we did encounter a few bugged moments where characters weren’t animated at all while their dialog played. All but one of these instances were brief enough to not take us completely out of the game though, thankfully.

“Flashback to classic adventure games.”

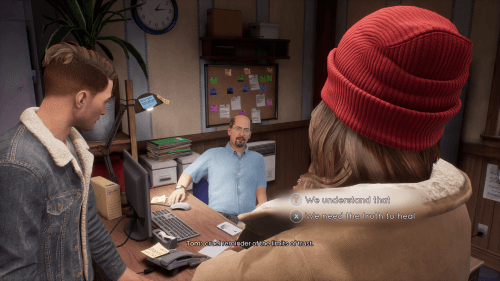

The bulk of my impressions were around the gameplay though. On the surface The Council seems to follow a Telltale-like take on the adventure game – a lot of dialog choices, decisions which appear to branch the storyline, and plenty of cutscenes. I’d say that there’s a lot more free roaming and even the odd inventory puzzle in The Council, and there are no real QTE scenes since there are no real action scenes, so this edges it a bit closer to the traditional point and click adventure game of the 90s. Where this gets interesting is that there is a layer of almost RPG-like mechanics on top of all of this: a skill-based system complete with experience points to advance those skills, traits that affect them, and using skills requires spending limited “effort points.” I was initially skeptical…

To go into that all in just a bit more detail, many of your dialog choices and some of your special actions in the game are tied to specific skills. Using these skills requires you to have the skill, of course, and the use of a set amount of effort points, which is reduced depending on what level your skill is at. You level these skills up as you gain experience from chapter to chapter, and there are also books that you can read in limited quantities each chapter, and traits which can sometimes grant you skill points as well. Interestingly, you will still see the options to use these skills even if you don’t have them, which can help guide you to where you might want to allocate skill points later, or in a subsequent playthrough, though every skill gets its turn sooner or later. Your pool of effort points grows as you level up, but can also be affected by items – you’ll find consumables that let you restore some of your points or even make your next skill use free. There’s also one that removes your alterations, which negatively affect the number of effort points you need to use a skill.

“The Council’s dialog system is surprisingly complex.”

The dialog system also has a few other surprises. First, there are “confrontations” which are special dialog events in which you need to choose the correct options in order to convince someone of something or win an argument, that kind of thing, and your success or failure will often cause a decision-like branching of the story. These all felt a lot more tense than normal conversations, even if the stakes weren’t particularly high. Confrontations are particularly affected by that character’s specific vulnerabilities and immunities to certain skills, which are usually discovered the hard way by choosing the wrong dialog option, though there’s another consumable that will temporarily reveal them to you. Finally, we have “opportunities” which are as close as The Council gets to Telltale’s QTEs – moments where you can, if you’re quick enough, move your cursor to an interactive hotspot that appears briefly, usually over part of the character you’re talking to’s face or body. These unlock special dialog or actions, often revealing new information, including vulnerabilities and immunities.

Overall, some of these systems were a bit bewildering at first, but in the end I think they work surprisingly well, and add a nice gamey component to the otherwise rather simple dialog system that most of these sorts of games employ.

Finally, there’s the story itself. If you’re the type of person who likes ancient and old world conspiracy theory along the lines of something like the Da Vinci Code, you might be as drawn in as I initially was. Right off the bat we have something of a “whodunit” mystery, all kinds of mysterious characters and related subplots, and a backdrop of political intrigue complete with secret societies attempting to pull the strings of events across the entire world. I constantly found myself wanting to learn more about what was really going on here, at least until the rather heavy-handed main reveal (something of a twist) comes in a later episode. While I found that twist, which brings in a supernatural element, and especially my character’s reactions to it to be a little silly, by then I was invested enough to say “fuck it” and just roll with it.

“Like I said, confrontations can feel a little tense…”

Unfortunately, the end of the game was a bit of a let down. There was a final confrontation which just… well, it just suddenly ended. As the game summed up how bad of a job we’d done in the last chapter and the post-game character wrap-up started to play, it took my partner and I a full 30 more seconds to realize what had just happened before we looked at each other and let out a simultaneous “OOOOOOooooooooohhhhh!” It was jarring enough that we did something we never do in these kinds of narrative games – loaded up our last save, corrected a mistake we made (an easy to miss but vital item we didn’t pick up) and went through it again, this time achieving a much better, even if it was similarly abrupt, ending. This does speak of one of the game’s strengths though, in that, not unlike The Quarry, there is a good amount of deviation and branching that can take place here, with over a dozen distinct endings. In fact, there was one major decision in the second to last chapter of the game that really had us debating amongst ourselves about which way to go, which should suggest it was an interesting and impactful one if nothing else.

That sums up The Council pretty well. Despite the weird, somewhat janky graphics and the plot that goes to some unexpected places, then ends faaaarrrr too abruptly, I enjoyed the game, especially its take on the narrative adventure mechanics, which has me suddenly much more curious about Vampire: The Masquerade – Swansong, a game that hadn’t really been on my radar even a little bit before.

Unfortunately my dumb ass didn’t take enough screenshots of any of these games, and some of the ones I did take contained spoilers, so instead I’ve opted to steal them from various random places on the net.