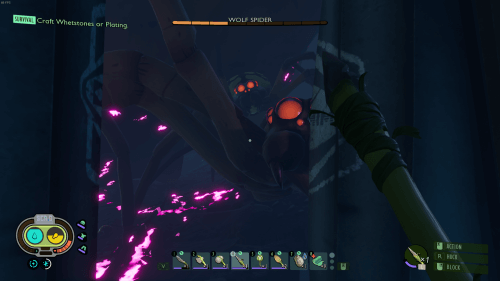

As I teased at the end of my original “Surviving Survival” article, Enshrouded was the next game on the menu. Seemingly along with a whole lot of others, previews of this game really caught my eye and I wasted no time jumping in by myself and exploring the world once it hit early access. While I liked what I played, I quickly decided to save it for a future cooperative playthrough, and it ended up being the next game my partner and I played after wrapping up Raft.

“First Steps into Enshrouded’s Embervale”

Unfortunately, this is going to be a pretty quick synopsis, because she totally bounced off of this game. I shouldn’t have been surprised as Enshrouded tends to feel much more action RPG or action-adventure heavy than your typical “tree-puncher” game, while she’s particularly into the building and decorating, as well as the crafting and organizing aspects of these games, often leaving much of the combat, exploration, and gathering up to me. She also commented on how she wanted to play a game where building bases actually has a purpose. That is, in Enshrouded, like in so many survival games, your base is simply a place to store your stuff and do your crafting and, at least up to where we played, serves very little other purpose. She specifically mentioned preferring 7 Days to Die, in which it’s critical that your base also becomes a stronghold due to its “Blood Moon” events and the ever-present threat of wandering zombies.

In retrospect, I guess Enshrouded does feel a bit more like a hybrid between a very adventure-forward, RPG-light action RPG – something like the Fable series, for example – combined with a more stereotypical voxel-based, open world crafting/survival game. I mean, don’t get me wrong, that sounds utterly fantastic to me, but I suppose I’m still trying to figure out exactly what really grabs her about the genre. Still, she’s played through Breath of the Wild and similar games, so I thought she might still find a lot to like in Enshrouded. Sadly, after a couple of sessions, she pretty much lost all interest. Personally, I know that Enshrouded has had something like 4 major patches since I first picked it up in February, so I’m sure it’s only continuing to get more content and develop its already fairly polished systems, and I enjoyed the 10 or so hours I’ve put into it so far, so I think I’ll be going back to it at some point. Whether I go back by myself, with her, or with our larger co-op group, who knows?

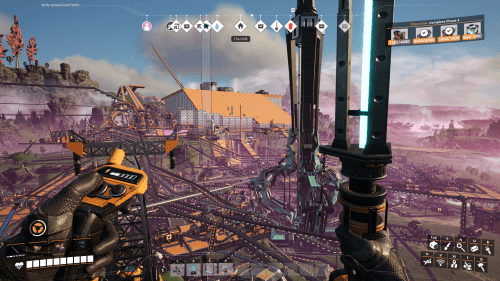

“A chaotic sprawl is practically unavoidable in late-game Satisfactory…”

Speaking of our larger group, after wrapping up Grounded, we decided to go for something a little different, and played through an entire run of Satisfactory. I’d never played Satisfactory, nor similar manufacturing focused games like Factorio, so this was all new to me. It’s perhaps a bit of a stretch to toss these types of games into the open world survival category, though there’s certainly a common lineage in my mind. That is, if Astroneer perfected the mindlessly enjoyable mining/gathering aspect of Minecraft’s survival mode, Satisfactory and its ilk are doing the same with late game large-scale crafting and automation, and personally, I fucking loved it!

Dropped onto a planet with practically nothing, the game generously drip feeds you your first string of goals, and soon you’ll have a base of operations and have extracted your first few types of resources. Very quickly, you’ll be installing automatic extractors and the means to power them, and automating getting those resources to your processing and manufacturing devices and/or storage containers… and that, well, that’s basically the whole game!

Satisfactory could very easily cut the umbilical right there and let you figure out how to move up the tech tree on your own, but instead it continues to push you forward via a series of milestones in which specific numbers of certain finished resources are shot up a space elevator in exchange for unlocking new recipes for new and upgraded machines and other gear to help you in your efforts to, of course, meet the next, even more demanding requirements. This progresses until the final couple of tiers have you manufacturing parts used to manufacture parts used to manufacture parts (and so on…) for end products that require multiple of sets of such complex components, turning your once humble factory footprint into a massive sprawl of extraction units, automated assembly, manufacturing machines, mazes of twisting conveyor belts, nuclear power plants belching waste, and delivery drones, trucks, and even trains darting about, blighting the once pristine landscape, while you keep focus on growing and especially optimizing every aspect of your operations.

“Have ramps, will travel.”

There’s also an exploration component of the gameplay, as the players have to explore to seek out more and more natural resources as the demands increase, and find special power-ups hidden throughout the world to increase your output. There’s also a slightly more free-form research component to go along with the milestone system which ties directly into that. Playing cooperatively provides the benefit of letting one or two people go on these scouting runs while others continue to focus on meeting the manufacturing tasks at hand. Building utterly ridiculous transportation systems to bring materials (or even finished components) from extremely remote harvesting sites and exploring some treacherous new biome looking for more cleverly hidden Power Slugs were some of my favorite parts of the game, in fact.

We ended up completing Satisfactory not long before the 1.0 patch was released, which would have added finished versions of some exploration related systems we only had placeholders for, and would likely make the final milestone tier a little less insane than what we went through (which eventually saw us just leaving our server up for a few days while as, close to as large and fully automated as we could will ourselves to get it, we let our collective factory run for hours and hours on end.) Apart from a few annoying bugs (like the often incredibly janky Hypertubes) the game felt finished enough, but had we known it was coming, I think we’d all have preferred to wait until the game was actually finished to do this play through. As it is, I think we’ll be back at some point to see what the actual ending looks like, and what other new goodies the developers add between now and then. All told though, I really enjoyed Satisfactory.

“*Cues Immigrant Song*”

After that, we decided to move back to more traditional territory, and headed to beautiful sunny grasslands and dark forests of Valheim. I talked a fair bit about Valheim in my first Surviving Survival post, though that playthrough was with a group of work friends rather than my normal weekly co-op group, so this was new territory for us. One of the other members of the group had played it before, though closer to its original early access release, and he and I dove right in with building a small village and exploring our surroundings. I think the other two members of our group, including my partner, struggled a little bit with the combat until we got a round or two of gear upgrades under our belts, but overall it seemed like everyone was getting to grips with the gameplay well enough.

Despite being ideally placed for the start of the game – that is, right on the sea and very close to big chunks of black forest and mountain biomes – the randomness of the map found us having to go on epic sea voyages to visit the swamps. Of course, we quickly established a forward base complete with a portal back to our village, but between that, and that biome’s less than friendly inhabitants (we were almost wiped by a Wraith at night more than once, and chased around the entire area by Abominations on several occasions) our group’s enjoyment of the game started to wane considerably, culminating in a group Sunken Crypt clear that went a little sideways, causing one of the party to need to make a seemingly impossible to solo corpse run multiple times, coming perilously close to resulting in a rage quit.

As with Enshrouded, it really wasn’t just the combat or the difficulty, but more something to do with the overall balance of combat, exploration, crafting, and base building (and I suppose how grindy all of the above feels, which can be a bit of an issue in Valheim) that didn’t sit quite well with my partner in particular. Specific complaints centered around the relatively unguided, sandboxy approach to game’s progression goals, and while I ultimately disagree, I can see where those complaints come from. I was disappointed, but it seems Valheim wasn’t quite the game for her either. Like Enshrouded, I would like to get back to Valheim again in the future, but it likely won’t be until the last big content patch is released, and perhaps even on a modded server as well.

“Green Hell? This doesn’t look so bad!”

It’s ironic then, after just mentioning potential struggles with difficulty, that my partner chose Green Hell as our next duo game. She’s been interested in Green Hell, as well as the similarly themed and probably better known The Forest, for quite some time, and that whole time I’d been a little worried about how much of a brutal exercise in survival it might be, as gleaned from various reviews. It turns out that my concern was warranted. While it wasn’t quite as unbearably difficult as it sounded, we definitely found it falling more on the side of frustrating than fun.

In Green Hell the players are thrown into the middle of the Amazonian rainforest. As is typical with these games, you’ll need to gather material to build tools and structures, hunt, fish, and forage for food, and deal with the sometimes less than friend wildlife. In Green Hell, we can add some rather aggressive native tribesmen, both real and imagined, to the list too. What I mean by “imagined” is that native attacks are often one of the end results of the kind of cool sanity system the game employs. That is, certain actions and conditions affect your sanity, making it, along with food and hydration, one of the basic stats you’ll need to keep track of in this game’s simulated version of survival. I mean that literally too, as even imagined native attacks will kill you. In fact, rather a lot of things in Green Hell will kill you. Just about everything you do, from sustaining a minor injury to simply picking up a rock or a log, or hell, even just moving around the environment, can result in some sort of negative status effect which, if not addressed, mostly by means of crafted healing items, can lead to a very bad time.

At first we decided to play the campaign, which does a fair job of justifying why in the hell you’re in the Amazon in the first place, as well as making the Waraha Tribe more than just an lazy depiction of native stereotypes, but after struggling with navigating the campaign’s tasks while dealing with the constant distraction of basic survival for a session or two, we opted to start over in sandbox mode so we could have more opportunity to learn the mechanics without the added pressures of the campaign’s objectives. Early on, we were fortunate enough to locate an abandoned camp relatively close to a river, and started rebuilding it, making it our base of operations as we got to grips with the basics. Soon, we’d learned to get enough fresh water and nutritious food for it to no longer be a massive burden and developed tools to be more and more efficient at gathering. Even after this new level of progress, things like the aforementioned negative effects could still feel like an annoyance at best.

“Never mind…”

Funnily, I think I was the one who was more frustrated this time around. While I would usually get into the game, at least for the first couple of hours of a session, I didn’t look forward to the prospect of playing it again, and at some point all of the struggles and random-feeling deaths started to just feel absurd. She finally came around when, feeling like we had things around our camp reasonably figured out, we decided to venture out, knowing that we’d yet to encounter some of the resources that would be required to continue to tech-up. We quickly ran into new, even more challenging wildlife, and found ourselves having to run back to our base to lick our wounds. Even after over 20 hours of gameplay, we kind of felt like failures.

To be clear, I’m not calling Green Hell a bad game. In fact, I’d hazard to guess that a harsher take on the survival genre was one of Creepy Jar’s goals here. I do think, however, that overcoming some of these challenges felt less rewarding, not to mention more ephemeral, than many of its contemporaries, which, personally, just didn’t provide the dopamine hit I needed to flip the switch from the gameplay loop feeling like a chore to being entertaining. With this genre, that’s probably a thinner line for most of us than we might think. That all said, even after all of this, I’d still really like to go back to the campaign and try to complete it. Unfortunately, by the time we reached that point, my partner was fully ready to move on.

“Sitting on the throne in Abiotic Factor more often means something very different.”

The next game our larger group played was Abiotic Factor. This was one I was entirely unfamiliar with, but everyone else seemed to think it looked fun. Personally, from the trailers I watched and the little bit I read, I really didn’t know what to expect. Scientists living in an underground bunker, having to craft new experimental devices to survive? I don’t know, I was getting some major Fallout and Silo vibes, though mixed with the primitive graphical style and odd mix of multiplayer scares and zaniness of Lethal Company. Okay…

Now that I’ve played it though, the premise of Abiotic Factor is easy enough to convey. You play as a random worker in a massive underground research facility that is researching… let’s just say, some very exotic things. You know, inter-dimensional portals and the new and lifeforms inhabiting them, that kind of thing. It’s your first day of work and, thanks to some impeccable timing, a major catastrophe occurs and you’re trapped inside as the facility goes into lock down. With almost everyone dead or evacuated and the facility in shambles, your objective is to survive long enough to find a way out. Now, if you’re getting Half Life vibes from this description, you’re right on the money. It seems like the first Half Life was a huge influence here, although, as implied by the comparison to Lethal Company, the whole thing is done in a decidedly less than serious way.

The writing is fun, from humorous voice lines to the fact that at times the size and scope of the facility almost feels more like parody than homage. This is also conveyed by some of the mechanics, like the fact that regular bathroom breaks, complete with a minigame to “ease the passage” are one of the survival elements you’ll need to manage. It’s also present in the graphics, which, particularly when it comes to human characters, border on being preposterous, which I’m fairly sure was intentional. For me, this quickly fell away, as the enemies and environments looked nice enough, and I found myself so immersed in the seriousness of the situation that we, as players, found ourselves in, that I forgot all about that aspect outside of the occasional moment of playful downtime back at our base.

“A Defense Robot versus a Composer?! *Grabs popcorn*”

Initially, the game had us exploring abandoned offices, looting anything we could find, tiptoeing around the alien creatures roaming the darkened facility corridors, and hiding for our lives wherever we could barricade ourselves in when night came. These early areas were fun, and definitely got us on the hook. From there, the temporary base we’d established was relocated to a better location and greatly expanded, and the breadcrumbs the narrative dropped for us to head to our next objectives were more than enough to keep us entertained. Despite these objectives quickly devolving into a treadmill of “Go here, no, sorry, go there instead!” like encounters, they led to some unexpected places, including some challenging navigational puzzles, very dangerous enemies, and some memorably tense and scary moments. Of those, Flathill, particularly the library, the damnable Hydroplant, and the deep-dive to the Neutrino Detector, immediately come to mind.

Mechanically, the game is more or less your typical open world crafting/survival game, though some of the decisions in how those pieces are assembled make Abiotic Factor feel like a fresh take to me. New recipes are learned when acquiring new materials, and then researched via a simple minigame where the player attempts to deduce which other components are required to craft the item. This is used quite cleverly to advance the narrative – a new material and/or recipe is introduced which will then require the players to seek out the other required components, which leads to having to explore new areas which in turn means overcoming new puzzles and enemies. Of course, the more exotic the materials you encounter, the crazier some of the items our team of mad scientists can cobble together become – this is not a game where you spend ages progressing from wooden spears to bronze spears to iron spears. In fact, in some ways, the item progression feels a bit more horizontal. It’s not all perfect – ammo for guns is scarce, perhaps being one of the few things you’d ever need to grind, and unless you’ve purposely built your character to use them, shooting them isn’t a whole lot of fun either. Similarly, many of the other items you get along the way feel like they’re of questionable use, though I’m sure this improves considerably with subsequent playthroughs.

“If your swimming pool yields unlimited fish it’s time to call a pool cleaner.”

Exploring is a big part of the gameplay. Thanks to being so in-step with the narrative, you’re always focusing on new parts of the sprawling facility. While travel time isn’t a huge issue (these areas are connected via a tram system to a central hub area) navigating some of these areas, between confusingly complex layouts and a less than generous in-game map, coupled with situationally respawning enemies can be, so it might make sense to build new, smaller bases in each area as you progress, leading to the more nomadic style of base-building that some other games in the genre, like Return to Moria, employ. For our playthrough, we ended up building our base so close to that central hub that we were able to just stick it out, making our excursions into other areas a major group event. It doesn’t seem like my partner, with her preference to hang back at base and work on building, crafting, and logistical matters, would be into this at all, but, thanks to an early agreement that we’d always try to stick close together when running missions, this really wasn’t an issue.

A lot of the other mechanics in the game are similar to other games in the genre too, of course. Besides your bathroom breaks, you need to manage your food and water, sleep/rest, and body temperature. The latter comes into play in some specific areas, where you may need to equip appropriate clothing to stay warm, or keep cool, but overall, none of these are too hard to manage. Food, for instance, feels like it is going to be a huge burden, but we quickly discovered how easy fishing was and, luckily, our base was situated right next to some water for extra convenience. Really, pretty much every challenge we ran into was soon met with some sort of solution to ease the burden, if not outright remove it. I’ve yet to play it myself, but I’ve seen many of the mechanics of this game compared to one of the early standouts of the genre, Project Zomboid, which it seems most people would consider high praise.

“Hey Project Zomboid, we’ve got zombies too!”

So, pretty much exceeding my expectations at every turn, the biggest negative about our experience with Abiotic Factor is actually how our playthrough ended. After struggling through the last area of the game, which definitely felt like a culmination of the gradual difficulty curve we’d felt up to then, the breadcrumbs just… stopped. You see, the game is still in early access, and not unlike Satisfactory, despite feeling reasonably polished the entire way through, simply wasn’t finished. The difference was that we knew we were reaching the end of Satisfactory, whereas Abiotic Factor just abruptly stops. We were left with no way forward and no conclusion to the story, our characters doomed to spend the rest of their lives trapped in the depths of the GATE Cascade Research Facility. That said, we definitely all enjoyed it enough to go back when there is more to do (one of our group, who plays a ton of games, even called it one of his games of the year) though I suspect we’ll be waiting for the game to exit early access before that happens.

That rounds up this game log, though naturally our group has already moved on, and we’re currently exploring the lush planet of Olympus in Icarus. Next time!

A few of these screenshots were swiped from the Steam Community, as I shamefully didn’t take enough good screenshots of my own. I need to get better at that. New Year’s Resolution?