Note: The screenshots posted on this page have been scaled up a little from their tiny native resolutions as well as had their aspect ratios corrected to proper 4:3 dimensions as they should have looked on CRT monitors originally. For posterity’s sake you can also click them to view the “pixel perfect” originals.

Introduction

If there is one genre of games that makes me extremely nostalgic it has to be the old, all but dead, genre of “graphical adventure games” that thrived on personal computers of all sorts and even hitting the occasional console in the mid 1980s to mid 1990s. When most people think of graphical adventure games they typically only think of the classics from Sierra and LucasArts but there were plenty of others out there of varying quality. The Hugo series (Hugo’s House of Horrors, Hugo II, Whodunit?, and Hugo III, Jungle of Doom) by Gray Design Associates, while far from one of the best, certainly had a large audience and long legs.

For the first year or two that I had my first “IBM compatible” PC I would often talk my parents into buying me inexpensive shareware and budget titles at various stores around our town. There was no way I was going to talk them into buying me a $50+ retail game on a whim but these cheap games? Sometimes that actually worked. Occasionally the games were even decent to boot. Of all of these often regrettable purchases I recall that several were published by the same company. Indeed these green Personal Companion Software boxes seemed to be just about everywhere that had computers for sale and over time I stocked up on several of them including at least one other title that I plan to review in the future. Getting to the point, this is how I first met the titular Hugo.

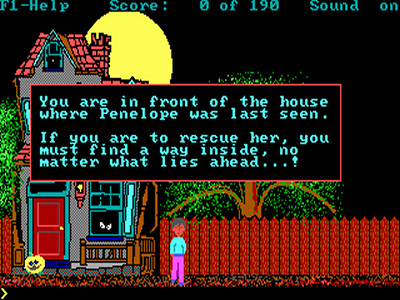

“The entire plot of the first game.”

Most people, I suspect, met Hugo a different way. The reason for the large audience and the fact that people still seem to play the games to this day is that, as was fairly common at the time, is that GDA originally released the Hugo trilogy as shareware. Unlike the majority of shareware titles, however, the Hugo games weren’t crippled in any way – there were no time limits, they weren’t missing any kind of content, there weren’t even annoying nag screens. These were the full games! It honestly seems like an odd move to me as the titles might as well of been Donationware though perhaps that was the intention from the start. And we thought we had it good getting the entire first episodes of Wolfenstein 3D and Doom for free!

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the Hugo games to me is that they were all created by one guy, David Gray. One guy managed to expertly emulate Sierra’s AGI classics. As someone who started learning to program just a few years later this seemed like quite an admirable accomplishment to me and still does. David Gray’s company, GDA, went on to release a fourth Hugo game in 1994 – this time resembling Wolfenstein 3D and again coded from scratch. I’m stumped over why this guy isn’t still out there coding awesome games.

The Hugo games weren’t my first adventure games, not by a long shot, and they’re definitely not my favorites but at the time I had all but written off graphical adventure games that maintained a text parser and these games really helped me begin to appreciate them again.

Gameplay

The gameplay is typical of the adventure game genre. The player guides the protagonist from screen to screen solving puzzles, the majority of which concern how to progress to the next screen. A great many of these puzzles involve collecting items from the game world and using them in conjunction with the environment or each other, sometimes in fairly creative ways. Like I said, typical adventure game stuff.

As with many other adventure games, particularly Sierra’s, points are awarded for certain actions, mostly pertaining to solving puzzles, and a total is displayed to you at all times to give you a clue of your progress. Many of these points are optional so it is entirely possible to beat the game without reaching the total. This, I always imagined, was there to provide a hint to players that they missed something and encourage them to attempt to explore and experiment more in subsequent playthroughs. I’ve never been someone who cared a great deal for “one hundred percenting” a game myself so I rarely pay too much mind to these scores.

“No, letting the mutant dog fuck your head isn’t actually the solution to this puzzle.”

The puzzles are most often fairly logical despite sometimes feeling a little abstract though there were a few cases while replaying the series without the aid of a walkthrough for this review in which I did indeed get stuck.

During the first game, for instance, I reached a room with a killer beast of a dog in it. If I entered the room he attacked me instantly. Along the way, however, I had picked up a piece of meat and what seemed to be a dog whistle. The whistle, when blown in the adjacent room, would summon the dog who would, again, attack me. I concluded that I needed to put the piece of meat on the floor and call the dog but no matter what I did the dog would ignore the meat. I experimented with this for what seemed like an hour before finally figuring out that I needed to simply enter the room the dog was in initially and quickly toss him the meat – the whistle served an entirely different purpose. Still, one would think if the dog was interested in the meat in one room he would be interested in the meat in another and it seemed more logical to me to distract the dog in a room other than the one I was trying to explore. Hmph.

A more frustrating thing about the games that was often a problem across the entire genre was the whole “oops, you missed that” thing. That is, finding out towards the end of the game that you missed grabbing a crucial item near the beginning of the game and now have to backtrack. In many cases backtracking might not even be possible – hope you have plenty of saved games! These kinds of conundrums can certainly be designed around but it isn’t surprising to see them in lower budget titles.

A silly example from the first game of getting caught in one of these situations is that early on you enter into a room with a character in it and an item on the table. The character eventually shrinks you but only temporarily. It wasn’t until after this scene was over that I tried to get the item on the table since the presence of the character seemed to take priority. I couldn’t get the item no matter what I tried as somehow I couldn’t reach it. I tried to position my character in numerous ways but eventually gave up. This item, of course, ended up being critical near the end of the game. I later discovered that I needed to pick up the item during the short time that I was in my shrunken state. I had to resort to an extremely old save and replay quite a few sections because of failing to recognize the puzzle at the right time, missing my only opportunity to get that crucial item. Doh.

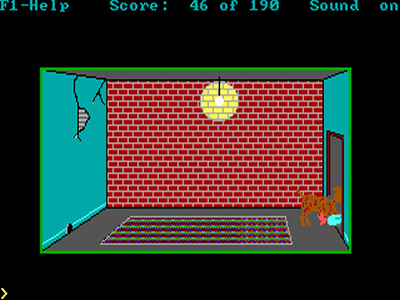

“As I entered his basement I was immediately impressed by the scope of his rock collection.”

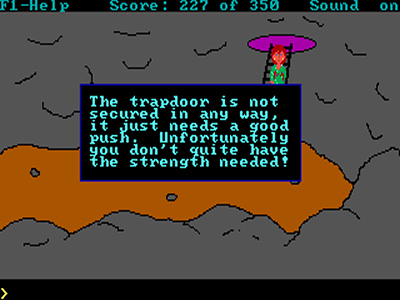

The games, particularly the second one, are pretty bad at pointing you in the right direction by giving you decent clues about what items are needed and where they might be found. In fact at times items seem to be pretty randomly dispersed through the game. In the third game there is a point at which, having exhausted all possible item uses and screens, the solution only lies in finding a hidden item by walking into the exact, out of the way spot in what would otherwise be an unremarkable area. This felt less like a puzzle and more like luck – I didn’t feel clever when I finally found the item, just annoyed about how stupid the solution ended up being.

The infamous Sierra style sudden deaths and other game ending events that are often only avoided by trial and error do occur in Hugo as well. Thankfully the ability to save and load your game at any time, as well as maintain a slew of saved games concurrently, helps to assure that you’re rarely too screwed over by this type of thing providing you have the discipline to “save and save often.”

What is more troubling is when these kinds of puzzles don’t actually result in any obvious problems for your character. There is an infamous puzzle in the second game that involves your character crossing a bridge. You must cross the bridge in order to proceed yet doing so usually results in you dropping an item into the creek you were crossing, ruining it. You can still pick the ruined item back up giving you the impression it still has some value but indeed it turns out to be a game crucial item that must remain undamaged. Even sillier is that what seems to be a scripted event in you dropping the item actually turns out to be a really horrible movement puzzle.

“The luxurious Château de Trace.”

Not so much a note about the quality of the puzzles in the game but still worth a mention is that there is an odd puzzle late in the first game in which an old man quizzes the player on a variety questions completely unrelated to the game. This might throw a lot of people off since some of the questions are fairly dated and somewhat esoteric in the first place. Apparently a lot of other people complained about this as well as the answers are in newer versions of the manual. The second game humorously mocks this puzzle by setting your character up for a repeat scenario only to have her interrupt and subdue the old man.

All of that being said if you enjoy graphical adventure games than you’ll be right at home with the Hugo games as you’ve most likely ran into and eventually learned to accept all of these annoyances decades ago.

Story

The setup for the first game, Hugo’s House of Horrors, is that Hugo needs to search a creepy looking mansion for his girlfriend Penelope who went missing after going there on a baby-sitting job. That is pretty much the entire story as, until the game actually ends, there is no real advancement in the plot. Though it might not have much to do with the story stuff does of course happen: you’ll get shrunk by a mad scientist, stumble upon a gathering of horror film villains, fight off a swarm of vampire bats, and fend off a mummy. While that list might sound impressive, this first game, even taking into account the time spent on the harder puzzles, is incredibly short.

All of the rest of the narrative elements of the game, from the setting to the characters, are ultimately very shallow. It is as if the author knew he wanted to make an adventure game but lacking a story instead settled on a genre he could easily barrow common themes from. On the bright side this comes across as intentional camp with the game even occasionally poking fun at itself. It definitely is humorous though usually in a much more subtle way than its Sierra and LucasArts counterparts – rather than every description and piece of dialog being hilarious I found myself more often chuckling at the bizarre situations I’d get Hugo into.

“My SJW senses are tingling!”

The second game in the series, Hugo II, Whodunit?, quickly replaces Hugo with Penelope as an Agatha Christie like murder mystery unfolds. In her quest to discover the identity of the murderer Penelope will seduce crusty old gardeners, wander aimlessly around massive hedge mazes, meet Doctor Who, summon genies, and slanderously accuse Hugo’s family members of murder left and right. As with Hugo’s House of Horrors it seems that the author simply picked an established genre and went with its tropes for content. This time he went with murder mystery instead of horror.

Hugo II, Whodunit? has even more of the self aware humor than the first game and is often less subtle about it. There’s also more humor period. One moment from Whodunit? that had my chuckling was when Penelope summons a rather unimpressive genie. Not only does he immediately demand food from Penelope but no wishes here – her only reward is him forcing open a stuck door in a decidedly less than magical way for her.

Unfortunately Whodunit? also suffers greatly from giving even fewer clues on where to go and what to do leading to some fairly abstract, if not totally illogical puzzles. That difficultly is compounded by the fact this is easily the longest of the Hugo games and features the most total screens. On the flipside the murder mystery story of Whodunit? is perhaps the most intriguing of the series with some actual plot development and even some twists. Nothing too spectacular but an improvement no doubt.

The third game in the series, Hugo 3, Jungle of Doom, finds Hugo and Penelope crash landed in a South American jungle and Penelope bitten by a poisonous spider. Hugo has to find the antidote and along the way kill indigenous people, drown elephants, bust some ghosts, and rock a sweet Tarzan impression. A tiny bit better on the plot development than Hugo’s House of Horrors but just as short, if not shorter.

At the end of the day the stories of all three games are just excuses for some fun, static settings to explore which will probably suit a lot of adventure gamers just fine. There are plenty of other adventure games out there with great narratives and excellent characters – these aren’t them. Still, it all works in an a way that harkens back to the earliest text adventure games. It’s less about the story or the characters and more about the puzzles and the experience losing yourself in an imaginary world to solve them.

Controls

All three of the Hugo games play exactly like clones of Sierra’s early AGI engine games. That is, you move your character with your keyboard’s arrow keys as you might in some other type of graphical game, yet all of your other interactions require typing commands into a text parser as you would in a text based adventure or interactive fiction game. Sometimes positioning your character exactly where you want them can be a tad bit annoying but for the most part you adapt to moving around rather quickly.

Your character’s “hitbox” can seem pretty oddly proportioned but there are few movement related puzzles in which you’ll ever notice thankfully. When you do run across them such as in the aggravating Venus Flytrap puzzle in Whodunit? you’ll be cursing up a storm though.

“Well, we might have crash landed but at least you haven’t been bitten by a poisonous spider.”

The text parser seems to be fairly generous with its synonyms not requiring the player to be as overly accurate with their terminology compared to some other, similar games. Occasionally the action picks up and given that this is a text command driven game sometimes moving quickly means frantically trying to type in a command and slap enter which can be pretty challenging, if not frustrating. Luckily across all 3 games these moments are relatively rare and a normal, leisurely adventure game pace is more frequently kept.

One of my only complaints about using this kind of a limited text interface, other than those moments of frantic, do or die typing I mentioned, is that sometimes you find yourself having to do a lot of typing with very little feedback. It can be pretty annoying having to type out several separate commands just to perform what is ultimately a simple task such as opening a door with a key. I’m sure this is one of the reasons that these kinds of games were quickly replaced by the point and click variety. I’ll talk more about text parsers when I review an interactive fiction title later down the line.

Graphics

The graphics of the series closely resemble those of other 1980s 16 color EGA adventure games. This isn’t really a compliment though, considering that the games were released in the early 1990s. The sprites and corresponding animations are universally simple, some might say bad even but I’m trying to be generous. 🙂 The background art has a bit more range though – many of the backgrounds show interesting perspectives and feature details which you can tell probably took a little time while others seem to have been completely uninspired and quickly hacked out. Jungle of Doom, with it’s abundance of lush jungle foliage, sports the best and most consistent backgrounds owing largely to another artist having contributed them.

“Alright, which one of these bastards gets it first?”

One could simply say “it’s EGA so it sucks, what else were you expecting?” but it isn’t quite as simple as that. The art in these games, while similar, lacks the cartoony stylization of many LucasArts titles and even the detail and refinement of Sierra titles. That being said, it is EGA so what were you expecting? 😉 Chances are if you can stomach any old EGA games you’ll be able to handle the Hugo series.

Sound

All three games use loud, harsh sounding PC speaker music and sound effects and do so at a minimum to boot. Music pops up only on occasion, such as in the first scene of the first game, and doesn’t ever stick around for very long. Sound effects are practically nothing more than beeps and blips and there aren’t many of those either. I’d suspect that many people simply preferred to play with the sound turned off.

Old Age

As usual I played all three games on my dedicated 486 gaming PC with the internal cache disabled (slowing it down to low end 386 speeds) and had absolutely no timing issues. I did briefly try to play the games without slowing my machine down and didn’t run into any obvious problems. I’ve not tried to run the games via DOSBox though all three have apparently been 100% supported for quite a few versions now. The games are also reported to be fully supported by ScummVM.

The un-crippled shareware versions of the games are readily available on many DOS and retro gaming sites. Here’s one, for instance. You can also purchase all three games, along with their Windows ports (which add MIDI music, real sound effects, and point and click controls – no I haven’t tried them!) from their original author’s site.

Update 8/2014: GOG.com now sells the Hugo Trilogy! They appear to be pre-configured to run in and bundled with ScummVM though they may be the Windows versions, if you care.

“At least one of these plants has GOT to get me high.”

Text file manuals come with both the shareware and full versions of the games though they’re not really needed. There are also numerous walkthroughs including spoiler free versions available for all three titles all over the place. GameFAQs is probably a good place to start.

Sequels and Related Games

As mentioned, GDA went on to release another Hugo game called “Nitemare-3D” which aped Wolfenstein 3D instead of Sierra adventure games. I never played this one as my main attraction to the Hugo games was the fact that they were adventure games. Still, Nitemare-3D is said to be more puzzle-y in nature than most of the FPS games from around that time. This game, along with the others, was also ported to Windows later.

Closing

The Hugo games aren’t spectacular but are fundamental graphical adventure games that should provide either fun trips down memory lane for people who loved Sierra’s old AGI games and their imitators or unique experiences for those who haven’t ever played anything similar. Each of the games can be completed within a couple of hours at the very most and since, unlike similar games, you can get them all for free without resorting to abandonware sites I’d suggest you check them out if they sound at all appealing. Just be prepared for what you’re getting into if this type of game is new to you.

The Hugo engine includes a feature called the “Boss Button” – a hot key that instantly pauses the game and swaps you out to a DOS prompt. Apparently David Gray got caught making games at work so often that he felt the need to help the rest of us avoid getting caught playing them. 😀